An Archive of Forgetting: Egypt, 2011-2021

[On 26 March 2021 the Centers for Middle East Studies at Harvard University and the University of California, Santa Barbara, as part of the yearlong collaborative project “Ten Years On: Mass Protests and Uprisings in the Arab World,” held a roundtable titled “Archives, Revolution, and Historical Thinking.” The persistence of demands for popular sovereignty throughout the Middle East and North Africa in the past decade, even in the face of re-entrenched authoritarianism, imperial intervention, and civil strife is a critical chapter in regional and global history. The following is one of several written contributions elaborating on the discussion addressing the relationship between archives, historical thinking, and revolution—both past and present. Click here to read the remaining contributions to this roundtable.]

It is so difficult to measure the passing of time we know is gone. Events that took months and occurred years ago are encapsulated in an image, a song, or the vivid recollection of euphoria; they seem to have happened yesterday, to be happening now, never to have happened at all. In some ways, the 2011 uprising in Egypt—shall we call it revolution? Perhaps, perhaps not—is ongoing. In others, it never was. The bitter sense of a stillborn revolution was born in the earliest days of the uprising, when observers discredited the popular protests as a possible cause for Hosni Mubarak stepping down. They asserted that this was, instead, the result of a decision in the army high command. As a historian, I have always grappled with causality. The 2011 uprisings dealt a blow to my confidence in understanding how a plethora of events could lead to a given outcome. What was that outcome, for that matter? Today, ten years on, as the Egyptian regime presides over a massive campaign to erase lived history and stake its claim as the sole gatekeeper of the past, the outcome seems clear. But in the months and years that followed the eighteen days it took to topple Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, radical uncertainty held sway, as Egyptians who had supported the uprising argued over various bad choices and weighed which course of action was least harmful—while wondering whether we were taking action at all.

Activists’ efforts to document and archive the uprising may have been in part a response to the multiple regime attempts to dismiss it as the work of “foreign hands” at worst, or as irrelevant at best. Activists archived the uprising as it took place through photographs, video footage, and recordings of songs and slogans to say that this is how it is, this is what we are doing, see what they are doing to us. It seemed essential not only to capture these moments but also to make them accessible to as many people as possible, on the ground and elsewhere: those sitting in their living rooms across the country—the hizb al kanaba (the couch party, or the silent majority) as they were then called—as well as those outside Egypt. It was especially important for activists to relay these revolutionary moments to people in other Arabic-speaking countries, many of whom either looked to Egypt for inspiration or asserted that their own revolutions were different, better, or somehow immune from the forces that dragged the country back to authoritarianism. This effort to archive the uprising was individual and collective. It was carried out by everyone and for everyone. The aim was to document what was occurring, not so much for future generations as for the rest of the country and the world at large, to show that people were being shot, to demonstrate solidarity, and to keep a record of the dizzying events.

At the same time, activists were fully aware of the historical importance of this archiving effort. Every bit of footage was evidence of what had occurred. They knew that the importance of archiving increased as time passed and as the narrative of the eighteen days began to change. Activists made themselves into historians of the future. Later, when YouTube videos such as those showing security forces firing live ammunition on activists began to disappear, it became clear that these archiving efforts were acts of resistance that depended as much on the collective (the internet) as it did on the individual (those who were on the ground, saw the snipers on downtown rooftops, lost an eye, or had footage on their phones). Collectives that had sprung up during the uprising, like the volunteer media activist group Mosireen, became the keepers of archives that burgeoned and grew while awaiting someone who could make sense of them. This opening of the archive concerned not only the modes of archival production but also the actors constituting them and the very way we came to think about what was worthy of archiving.

In turn, the counterrevolution led to a closure of the archives that affected these same modalities. As a result, the very act of documenting the quotidian became a security threat. Taking photographs of buildings in Cairo on my phone the other day, I was immediately approached by security personnel who demanded that I delete them. Thus, those who could have been historians of the present moment—who could have archived the disappearance of revolutionary spaces and shown how new realities demolished the past decisively, who could have preserved a memory of what underlay the totalitarian spectacle we are watching today—are forced into the position of furtive observers, exiled by highways and barricades from histories they remember vividly. The combined urgency and impossibility of documenting an urban reality as it disappears are almost unbearable at times. What can withstand the narrative of inexorable progress, of the army as the savior of the revolution.

It is so difficult to measure the passing of time we know is gone. Events that took months and occurred years ago are encapsulated in an image, a song, or the vivid recollection of euphoria; they seem to have happened yesterday, to be happening now, never to have happened at all. In some ways, the 2011 uprising in Egypt—shall we call it revolution? Perhaps, perhaps not—is ongoing. In others, it never was. The bitter sense of a stillborn revolution was born in the earliest days of the uprising, when observers discredited the popular protests as a possible cause for Hosni Mubarak stepping down. They asserted that this was, instead, the result of a decision in the army high command. As a historian, I have always grappled with causality. The 2011 uprisings dealt a blow to my confidence in understanding how a plethora of events could lead to a given outcome. What was that outcome, for that matter? Today, ten years on, as the Egyptian regime presides over a massive campaign to erase lived history and stake its claim as the sole gatekeeper of the past, the outcome seems clear. But in the months and years that followed the eighteen days it took to topple Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, radical uncertainty held sway, as Egyptians who had supported the uprising argued over various bad choices and weighed which course of action was least harmful—while wondering whether we were taking action at all.

Activists’ efforts to document and archive the uprising may have been in part a response to the multiple regime attempts to dismiss it as the work of “foreign hands” at worst, or as irrelevant at best. Activists archived the uprising as it took place through photographs, video footage, and recordings of songs and slogans to say that this is how it is, this is what we are doing, see what they are doing to us. It seemed essential not only to capture these moments but also to make them accessible to as many people as possible, on the ground and elsewhere: those sitting in their living rooms across the country—the hizb al kanaba (the couch party, or the silent majority) as they were then called—as well as those outside Egypt. It was especially important for activists to relay these revolutionary moments to people in other Arabic-speaking countries, many of whom either looked to Egypt for inspiration or asserted that their own revolutions were different, better, or somehow immune from the forces that dragged the country back to authoritarianism. This effort to archive the uprising was individual and collective. It was carried out by everyone and for everyone. The aim was to document what was occurring, not so much for future generations as for the rest of the country and the world at large, to show that people were being shot, to demonstrate solidarity, and to keep a record of the dizzying events.

At the same time, activists were fully aware of the historical importance of this archiving effort. Every bit of footage was evidence of what had occurred. They knew that the importance of archiving increased as time passed and as the narrative of the eighteen days began to change. Activists made themselves into historians of the future. Later, when YouTube videos such as those showing security forces firing live ammunition on activists began to disappear, it became clear that these archiving efforts were acts of resistance that depended as much on the collective (the internet) as it did on the individual (those who were on the ground, saw the snipers on downtown rooftops, lost an eye, or had footage on their phones). Collectives that had sprung up during the uprising, like the volunteer media activist group Mosireen, became the keepers of archives that burgeoned and grew while awaiting someone who could make sense of them. This opening of the archive concerned not only the modes of archival production but also the actors constituting them and the very way we came to think about what was worthy of archiving.

In turn, the counterrevolution led to a closure of the archives that affected these same modalities. As a result, the very act of documenting the quotidian became a security threat. Taking photographs of buildings in Cairo on my phone the other day, I was immediately approached by security personnel who demanded that I delete them. Thus, those who could have been historians of the present moment—who could have archived the disappearance of revolutionary spaces and shown how new realities demolished the past decisively, who could have preserved a memory of what underlay the totalitarian spectacle we are watching today—are forced into the position of furtive observers, exiled by highways and barricades from histories they remember vividly. The combined urgency and impossibility of documenting an urban reality as it disappears are almost unbearable at times. What can withstand the narrative of inexorable progress, of the army as the savior of the revolution.

Tahrir Square is a caricature of this process of eradication, recast in the image of totalitarian spectacle. The “Golden Parade of the Mummies,” which ostensibly celebrated the transport of royal mummies from their home in the Egyptian Museum in Tahrir to the new Museum of Egyptian Civilization in Fustat, was covered by the media in March/April 2021 as a major national event. The massive pageant was a public relations triumph for the regime, not least because it now overlays the iconic images of Tahrir that were captured in 2011. The event, however, did not warrant a multimillion-dollar extravaganza involving celebrity soundbites about the pharaohs, a philharmonic orchestra, and elaborate choreographies. The parade encapsulated the uses of history for this regime: packaged for tourist consumption, conscripting natives as performers and sycophantic spectators, and requiring absolute control over narrative, representation, and space. History, in this sense, is a monolith antithetical to revolution; the selection and presentation of the past, repurposed to serve the regime’s purposes, ensures that spectacle is everything, pure form without substance. In contrast, Tahrir in 2011 was occupied by a plethora of narrators, an eruption of stories, uncontrolled and unpredictable. The process of archiving events was frenetic, chaotic, anonymous, and open source. The messiness of the archiving process was all the more obvious in light of the tightly choreographed parade of 2021, embodying as it did the “fetish of high resolution” and created with a television audience in mind. If 2011 can be reduced to a desperate and always unattainable attempt to capture the changing present and project it into the future, 2021 is a drive to foist the already archived ancient past onto the presumed needs and desires of the living. The museum, as pad.ma says, is where art goes to die.

When did the uprising end? There was, of course, no single moment. In a way, the uprising is ongoing. One can see it in the ways young people socialize, the questions they ask, and the taboos they disregard or never learned. Yet in others, the revolutionary moment is well and truly done, as if the definitive rupture had occurred not in 2011 but in 2013, in Rabaa Square. It was necessary to break with the past in order to imagine the uprising, to believe in it, since it posited a future that was by definition impossible after thirty years of Mubarak’s rule. Revolution as an epistemic break entailed the willingness to forego our understanding of the elements that make up historical thinking: change over time, causality, context, complexity, and contingency. It entailed the ability to believe that change could happen suddenly and that immovable structures could be dislodged. The epistemic break also entailed the ability to believe that the convoluted political context could contain spaces of freedom to act and that the simplicity of popular anger could dislodge a seemingly immovable object. But the counterrevolutionary period also defies historical thinking in the regime’s deliberate erasure of the past and its endeavor to lay exclusive claim to defining history and what may be admitted as such.

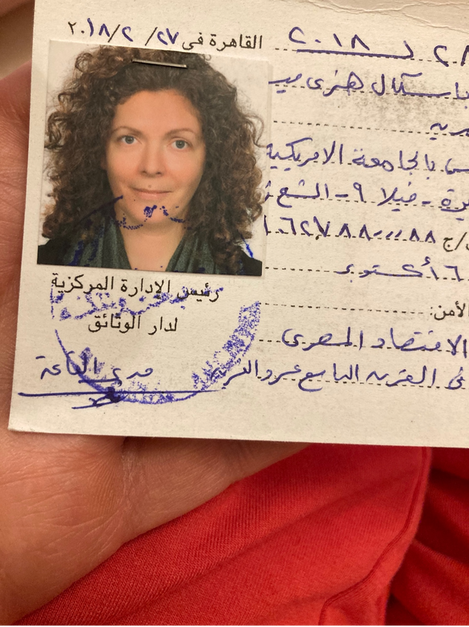

In a sense, we can narrate revolution and counterrevolution through archival access and archival practice. The document I share here, my permit from the Egyptian National Archives, documents my two-year struggle to enter the repository. By the time I received the permit, I was barely able to use it. The document stands in for the manifold stories that can no longer be told about the past. The state sealing of the archives has closed the possibility of thinking historically. A regime suspicious of historians is one that recognizes the threat of alternative pasts, of silenced voices, of secrets and surprises hiding in the archive. It recognizes the power of maps, deeds of ownership, and police informers’ reports. It knows that state security records were the blueprint for the structure of government that the army has confiscated over the past seven years. Archives in the hands of private individuals threatened to derail the Tiran and Sanafir deal with Saudi Arabia. They allow us to remember events that the current regime seeks to absorb and dissolve into an inexorable present. School textbooks can be rewritten to magically expunge inconvenient histories, people can be jailed and silenced, the records of defeats and executions can be locked away.

Yet among the subterranean outcomes of 2011 was a renewed interest in individual lives and private archives, documenting neighborhood histories, looking to oral accounts of the recent past for evidence of events that left no written trace. This clamor of subaltern voices constitutes alternative archives, incoherent and fragmented, no doubt, but pointing to possible futures in which the past belongs to all of us.

When did the uprising end? There was, of course, no single moment. In a way, the uprising is ongoing. One can see it in the ways young people socialize, the questions they ask, and the taboos they disregard or never learned. Yet in others, the revolutionary moment is well and truly done, as if the definitive rupture had occurred not in 2011 but in 2013, in Rabaa Square. It was necessary to break with the past in order to imagine the uprising, to believe in it, since it posited a future that was by definition impossible after thirty years of Mubarak’s rule. Revolution as an epistemic break entailed the willingness to forego our understanding of the elements that make up historical thinking: change over time, causality, context, complexity, and contingency. It entailed the ability to believe that change could happen suddenly and that immovable structures could be dislodged. The epistemic break also entailed the ability to believe that the convoluted political context could contain spaces of freedom to act and that the simplicity of popular anger could dislodge a seemingly immovable object. But the counterrevolutionary period also defies historical thinking in the regime’s deliberate erasure of the past and its endeavor to lay exclusive claim to defining history and what may be admitted as such.

In a sense, we can narrate revolution and counterrevolution through archival access and archival practice. The document I share here, my permit from the Egyptian National Archives, documents my two-year struggle to enter the repository. By the time I received the permit, I was barely able to use it. The document stands in for the manifold stories that can no longer be told about the past. The state sealing of the archives has closed the possibility of thinking historically. A regime suspicious of historians is one that recognizes the threat of alternative pasts, of silenced voices, of secrets and surprises hiding in the archive. It recognizes the power of maps, deeds of ownership, and police informers’ reports. It knows that state security records were the blueprint for the structure of government that the army has confiscated over the past seven years. Archives in the hands of private individuals threatened to derail the Tiran and Sanafir deal with Saudi Arabia. They allow us to remember events that the current regime seeks to absorb and dissolve into an inexorable present. School textbooks can be rewritten to magically expunge inconvenient histories, people can be jailed and silenced, the records of defeats and executions can be locked away.

Yet among the subterranean outcomes of 2011 was a renewed interest in individual lives and private archives, documenting neighborhood histories, looking to oral accounts of the recent past for evidence of events that left no written trace. This clamor of subaltern voices constitutes alternative archives, incoherent and fragmented, no doubt, but pointing to possible futures in which the past belongs to all of us.