Archives as Repositories of Resistance: Syrian Uprisings Past and PresentBy Reem Bailony

|

[On 26 March 2021 the Centers for Middle East Studies at Harvard University and the University of California, Santa Barbara, as part of the yearlong collaborative project “Ten Years On: Mass Protests and Uprisings in the Arab World,” held a roundtable titled “Archives, Revolution, and Historical Thinking.” The persistence of demands for popular sovereignty throughout the Middle East and North Africa in the past decade, even in the face of re-entrenched authoritarianism, imperial intervention, and civil strife is a critical chapter in regional and global history. The following is one of several written contributions elaborating on the discussion addressing the relationship between archives, historical thinking, and revolution—both past and present. Click here to read the remaining contributions to this roundtable.]

The revolutionary impulse of the 2011 Arab uprisings led me to a past moment of revolution—the Great Syrian Revolt of 1925. In the summer of 2011, I was preparing to do fieldwork on a project on gender and education in the Ottoman Levant when the start of the Syrian uprising prevented travel to Damascus. Instead, I went to the Library of Congress, where I came across the journals of the Syrian diaspora. Like the contemporary Syrian Americans who energetically kept vigil in the hopeful early days of Syria’s protests, in late 1925, diaspora journalists wrote daily about the anti-colonial revolt against the French Mandatory government. With the heaviness of the present weighing on me, I shifted my research to the transnational reach of the Syrian diaspora in 1925.

Like many Syrians witnessing the present, I grappled with how to narrate a failed revolution. This struggle played out in unforeseen ways in the archives as I navigated the persistence of injustice. I turned to the League of Nations archive in Geneva, where countless Syrian petitions and telegrams from all over the world protesting the French Mandate in Syria and Lebanon greeted me. Many were ignored. The Permanent Mandates Commission dictated that petitions from the Mandatory territory would be first vetted by the Mandatory regime. Diasporic Syrians avoided this mediation, gaining a disproportionate voice in the League minutes. Their counterparts in Syria, engaged in armed struggle and civil disobedience, were silenced. It was these folds of European liberalism’s constitutive contradictions that informed my search. At the same time, I came to understand how archives sustain revolutionary moments beyond the binaries of success and failure, triumph and defeat.

Revisionist histories of the League point to colonized people’s petitions as evidence of the proliferation of liberal values, or an indication of liberal internationalist discourse of self-determination, progress, and international justice.[1] A closer reading of petitions reveals much more than a simple mimesis of some higher universal ideal propagated by the League and its structurally exclusionary character. Syrian revolutionaries did not proliferate the League’s language. They shaped an alternative internationalism that challenged and critiqued the League and its liberalism.[2]

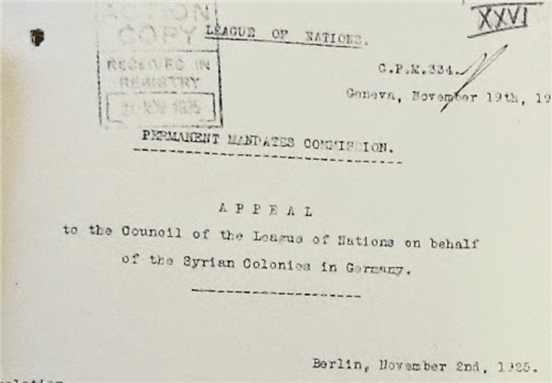

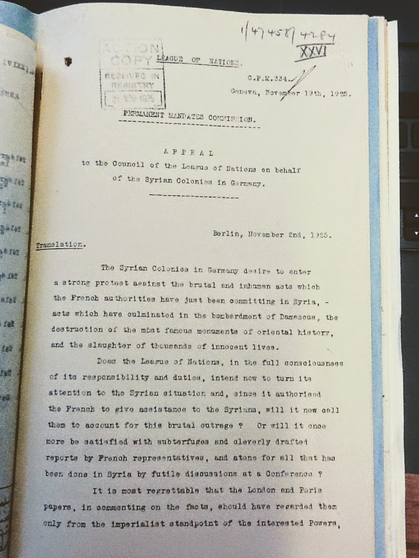

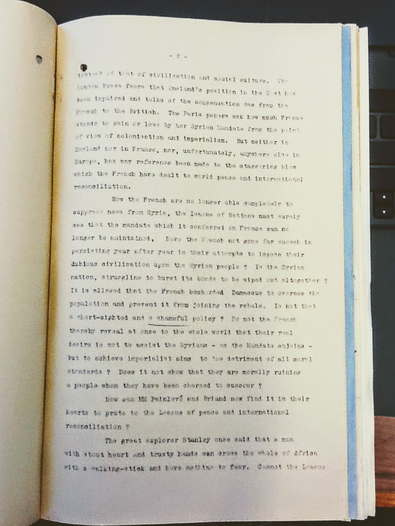

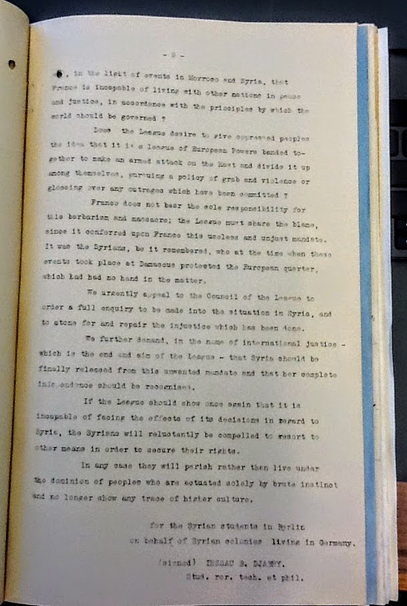

The archive’s inadvertent sustenance of revolution is evident, for example, in an appeal by Syrians in Berlin protesting the French Mandate’s bombardment of Damascus in October 1925. This forty-eight-hour assault killed thousands of civilians and irrevocably ruined historical sites (Figure 1).[3] Ihsan al-Jabiri, an Aleppan exile and one of the Berliner petitioners, admonished France for its brutal force in Syria. He condemned the League’s complicity in this injustice. Addressing the League Council, Jabri asked whether the League would continue its endorsement of France’s hollow response to public demands for justice.[4] Elsewhere, Jabri rebuked the British and French press for upholding imperialist politics rather than their ostensible aims to realize “civilization and social culture.” He accused France of imposing a “dubious civilization” in Syria. For Jabri, the League was a group “of European powers banded together to make an armed attack on the East.” France was not the sole responsible party for “barbarism” and massacre. Indeed, “the League must share the blame.” Speaking on behalf of Syrians in Germany, Jabri demanded that the League uphold its purported aspiration of international justice. In the Arabic-language press, Syrians pondered the utility of the petitions they were sending. They understood these exercises as far from the power and weight of a gun. At the same time, they understood these petitions as archiving an important historical moment. This archival power was itself a patriotic duty.[5] Jabri and his contemporaries demonstrated their own interpretation of the League’s spirit that reflected more than a simple adoption of the value of international justice but rather an ownership over its meanings and application.[6]

The revolutionary impulse of the 2011 Arab uprisings led me to a past moment of revolution—the Great Syrian Revolt of 1925. In the summer of 2011, I was preparing to do fieldwork on a project on gender and education in the Ottoman Levant when the start of the Syrian uprising prevented travel to Damascus. Instead, I went to the Library of Congress, where I came across the journals of the Syrian diaspora. Like the contemporary Syrian Americans who energetically kept vigil in the hopeful early days of Syria’s protests, in late 1925, diaspora journalists wrote daily about the anti-colonial revolt against the French Mandatory government. With the heaviness of the present weighing on me, I shifted my research to the transnational reach of the Syrian diaspora in 1925.

Like many Syrians witnessing the present, I grappled with how to narrate a failed revolution. This struggle played out in unforeseen ways in the archives as I navigated the persistence of injustice. I turned to the League of Nations archive in Geneva, where countless Syrian petitions and telegrams from all over the world protesting the French Mandate in Syria and Lebanon greeted me. Many were ignored. The Permanent Mandates Commission dictated that petitions from the Mandatory territory would be first vetted by the Mandatory regime. Diasporic Syrians avoided this mediation, gaining a disproportionate voice in the League minutes. Their counterparts in Syria, engaged in armed struggle and civil disobedience, were silenced. It was these folds of European liberalism’s constitutive contradictions that informed my search. At the same time, I came to understand how archives sustain revolutionary moments beyond the binaries of success and failure, triumph and defeat.

Revisionist histories of the League point to colonized people’s petitions as evidence of the proliferation of liberal values, or an indication of liberal internationalist discourse of self-determination, progress, and international justice.[1] A closer reading of petitions reveals much more than a simple mimesis of some higher universal ideal propagated by the League and its structurally exclusionary character. Syrian revolutionaries did not proliferate the League’s language. They shaped an alternative internationalism that challenged and critiqued the League and its liberalism.[2]

The archive’s inadvertent sustenance of revolution is evident, for example, in an appeal by Syrians in Berlin protesting the French Mandate’s bombardment of Damascus in October 1925. This forty-eight-hour assault killed thousands of civilians and irrevocably ruined historical sites (Figure 1).[3] Ihsan al-Jabiri, an Aleppan exile and one of the Berliner petitioners, admonished France for its brutal force in Syria. He condemned the League’s complicity in this injustice. Addressing the League Council, Jabri asked whether the League would continue its endorsement of France’s hollow response to public demands for justice.[4] Elsewhere, Jabri rebuked the British and French press for upholding imperialist politics rather than their ostensible aims to realize “civilization and social culture.” He accused France of imposing a “dubious civilization” in Syria. For Jabri, the League was a group “of European powers banded together to make an armed attack on the East.” France was not the sole responsible party for “barbarism” and massacre. Indeed, “the League must share the blame.” Speaking on behalf of Syrians in Germany, Jabri demanded that the League uphold its purported aspiration of international justice. In the Arabic-language press, Syrians pondered the utility of the petitions they were sending. They understood these exercises as far from the power and weight of a gun. At the same time, they understood these petitions as archiving an important historical moment. This archival power was itself a patriotic duty.[5] Jabri and his contemporaries demonstrated their own interpretation of the League’s spirit that reflected more than a simple adoption of the value of international justice but rather an ownership over its meanings and application.[6]

The Syrian revolt against the French was brutally suppressed and came to an end two years later, in 1927. The uprising did not shake French colonial rule in Syria. In the coming decades, elite nationalist politics marginalized the rebels. How can we make sense of this failure while still learning from Syrian petitioners? Is it enough that global Syrians poked holes in European liberalism? Or does it suffice that they created an archive of resistance, an alternative reading and history of the League and liberal internationalism?

In March 2011, Syrians took to social media to commemorate the ten-year anniversary of the Syrian uprising.[7] Some mourned the early days of hopeful protests before the revolution warped into unrecognizable horror and catastrophe. For others, the revolutionary moment was an ongoing project sustained by the citizen journalists and artists who documented it. These reflections and positions will shape how the revolution is remembered, narrated, and archived.

Like the petitioners of the 1920s, Syrians today are immersed in a struggle to shape the narrative of the revolution amidst competing forces on a broad political spectrum. Syrian-led initiatives like the Berlin-based Syrian Archive seek to verify, preserve, and investigate digital documentation of human rights abuses “committed by all parties to conflict in Syria for use in advocacy, justice, and accountability.” Since 2017, YouTube and Facebook have changed their content policies and algorithms to curtail “violent” videos and content, in part under pressure from the European Union to combat related extremism to the Islamic State in Syria (ISIS). As a result, thousands of invaluable digital sources documenting war crimes in Syria have been inadvertently erased.[8] The Syrian Archive aims to preserve this digital material. This content is crucial evidence in legal cases like the ongoing Syrian torture trial taking place in Koblenz. Another example, the Creative Memory of the Revolution, seeks to preserve and expand the creative openings that the 2011 Syrian uprising made possible. By sorting through and archiving the intellectual, artistic, and cultural expressions of the Syrian people during the uprising, the project hopes to sustain artistic and cultural resistance in repressive times.

Archives are spaces where revolution can exist in all its complexity, beyond the narrow confines of success and failure. They preserve alternate possibilities in which failure was not an inevitability. The historiographic task is to treat different moments of revolution in their unique specificity and to honor the smaller events, phenomena, and figures populating its aspirations, in the past and in the present.

Footnotes:

[1] On Mandates system, see: Susan Pedersen, The Guardians: The League of Nations and the Crisis of Empire (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015). On the League of Nations, see: Simon Jackson and Alanna O'Malley, eds., The Institution of International Order: From the League of Nations to the United Nations (Routledge, 2018). On liberal internationalism, see: Philippa Heatherington and Glenda Sluga, “Liberal and Illiberal Internationalism,” Journal of World History 31, no. 1 (2020): 1-9; and David Petruccelli, "The Crisis of Liberal Internationalism: The Legacies of the League of Nations Reconsidered," Journal of World History 31, no. 1 (2020): 111-136.

[2] See the AHR Reflection, “One Hundred Years of Mandates,” American History Review 124, no. 5 (December 2019); in particular, see: Sherene Seikaly, “The Matter of Time,” The American Historical Review, 124, no. 5 (December 2019): 1681–1688; and Sean Andrew Wempe, “A League to Preserve Empires: Understanding the Mandates System and Avenues for Further Scholarly Inquiry,” The American Historical Review, 124, no. 5 (December 2019): 1723–1731.

[3] For more on the bombardment, see Michael Provence, The Great Syrian Revolt and the Rise of Arab Nationalism (Austin: University of Texas, 2005).

[4] League of Nations Archive (LNA), R23, “Appeal to the Council of the League of Nations on behalf of the Syrian Colonies in Germany,” (2 November 1925).

[5] “Surat al-Ihtijaj al-marfu‘ ila ra’is al-wilayat al-mutahida,” Mir’at al-Gharb (20 November 1925).

[6] Natasha Wheatley, “Mandatory Interpretation: Legal Hermeneutics and the New International Order in Arab and Jewish Petitions to the League of Nations,” Past and Present (May 2015).

[7] Kareem Shaheen, “Opinion: I Watched Syrians on Clubhouse Grapple with their Failed Revolution,” The National (18 March 2021).

[8] Avi Asher-Schapiro and Ban Barkawi, “‘Lost memories’: War crimes evidence threatened by AI moderation,” Reuters (19 June 2020), https://www.reuters.com/article/us-global-socialmedia-rights-trfn-idUSKBN23Q2TO.

In March 2011, Syrians took to social media to commemorate the ten-year anniversary of the Syrian uprising.[7] Some mourned the early days of hopeful protests before the revolution warped into unrecognizable horror and catastrophe. For others, the revolutionary moment was an ongoing project sustained by the citizen journalists and artists who documented it. These reflections and positions will shape how the revolution is remembered, narrated, and archived.

Like the petitioners of the 1920s, Syrians today are immersed in a struggle to shape the narrative of the revolution amidst competing forces on a broad political spectrum. Syrian-led initiatives like the Berlin-based Syrian Archive seek to verify, preserve, and investigate digital documentation of human rights abuses “committed by all parties to conflict in Syria for use in advocacy, justice, and accountability.” Since 2017, YouTube and Facebook have changed their content policies and algorithms to curtail “violent” videos and content, in part under pressure from the European Union to combat related extremism to the Islamic State in Syria (ISIS). As a result, thousands of invaluable digital sources documenting war crimes in Syria have been inadvertently erased.[8] The Syrian Archive aims to preserve this digital material. This content is crucial evidence in legal cases like the ongoing Syrian torture trial taking place in Koblenz. Another example, the Creative Memory of the Revolution, seeks to preserve and expand the creative openings that the 2011 Syrian uprising made possible. By sorting through and archiving the intellectual, artistic, and cultural expressions of the Syrian people during the uprising, the project hopes to sustain artistic and cultural resistance in repressive times.

Archives are spaces where revolution can exist in all its complexity, beyond the narrow confines of success and failure. They preserve alternate possibilities in which failure was not an inevitability. The historiographic task is to treat different moments of revolution in their unique specificity and to honor the smaller events, phenomena, and figures populating its aspirations, in the past and in the present.

Footnotes:

[1] On Mandates system, see: Susan Pedersen, The Guardians: The League of Nations and the Crisis of Empire (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015). On the League of Nations, see: Simon Jackson and Alanna O'Malley, eds., The Institution of International Order: From the League of Nations to the United Nations (Routledge, 2018). On liberal internationalism, see: Philippa Heatherington and Glenda Sluga, “Liberal and Illiberal Internationalism,” Journal of World History 31, no. 1 (2020): 1-9; and David Petruccelli, "The Crisis of Liberal Internationalism: The Legacies of the League of Nations Reconsidered," Journal of World History 31, no. 1 (2020): 111-136.

[2] See the AHR Reflection, “One Hundred Years of Mandates,” American History Review 124, no. 5 (December 2019); in particular, see: Sherene Seikaly, “The Matter of Time,” The American Historical Review, 124, no. 5 (December 2019): 1681–1688; and Sean Andrew Wempe, “A League to Preserve Empires: Understanding the Mandates System and Avenues for Further Scholarly Inquiry,” The American Historical Review, 124, no. 5 (December 2019): 1723–1731.

[3] For more on the bombardment, see Michael Provence, The Great Syrian Revolt and the Rise of Arab Nationalism (Austin: University of Texas, 2005).

[4] League of Nations Archive (LNA), R23, “Appeal to the Council of the League of Nations on behalf of the Syrian Colonies in Germany,” (2 November 1925).

[5] “Surat al-Ihtijaj al-marfu‘ ila ra’is al-wilayat al-mutahida,” Mir’at al-Gharb (20 November 1925).

[6] Natasha Wheatley, “Mandatory Interpretation: Legal Hermeneutics and the New International Order in Arab and Jewish Petitions to the League of Nations,” Past and Present (May 2015).

[7] Kareem Shaheen, “Opinion: I Watched Syrians on Clubhouse Grapple with their Failed Revolution,” The National (18 March 2021).

[8] Avi Asher-Schapiro and Ban Barkawi, “‘Lost memories’: War crimes evidence threatened by AI moderation,” Reuters (19 June 2020), https://www.reuters.com/article/us-global-socialmedia-rights-trfn-idUSKBN23Q2TO.